Is it legal to set up a Web3 studio to help project parties make markets (liquidity services)?

By Lawyer Shao Shiwei (Twitter: @lawyershao)

The 2017 "94 Announcement" and the 2021 "924 Notice" have made it clear that initial coin offerings (ICOs) are prohibited in China, and virtual currency trading is considered illegal financial activity. Almost everyone in the industry is well aware of this.

However, in reality, a large number of Web3 studios are still active in the market, developing businesses around virtual currencies and Web3. Lawyer Shao often receives similar inquiries in his daily work:

- “If we allow a large number of users to register exchange accounts in a paid manner and profit from the commissions they receive for attracting new users, is there any risk?”

- “If I acquire a large number of user accounts and then help the project build a liquidity pool on a DEX in exchange for service fees, would this cross the red line?”

- "If I post contract tutorials in a QQ, WeChat, or Telegram group chat to recruit sub-agents and users for an exchange and receive commissions from the exchange's settlement, is this considered illegal?"

These questions have arisen frequently in legal consultations in recent years. I've previously written articles analyzing these issues (e.g., "What are the potential criminal risks associated with soliciting people to trade cryptocurrencies and manipulating contracts?" and "Is cryptocurrency influencers offering commissions for referrals legal?").

What we will focus on today is a typical scenario: "The studio uses a large number of accounts to create liquidity for the project party and collects remuneration" - is there any legal risk?

Meme coin issuance and fake liquidity: A common scam in Chinese projects

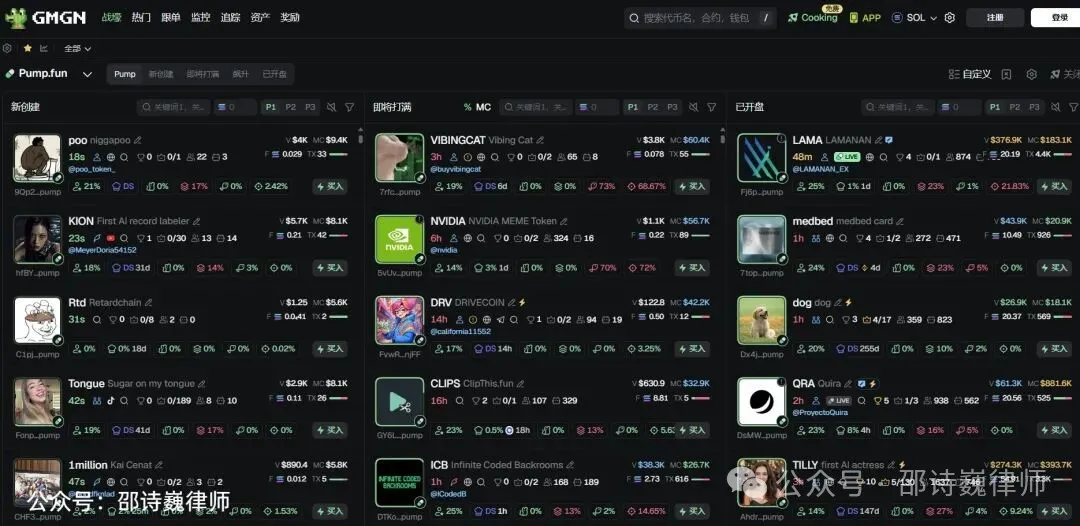

Open GMGN (a one-stop platform dedicated to on-chain meme coin transactions and analysis), and you will find that meme coins are updated almost every second. So are there Chinese issuers of these tokens? Definitely, and in astonishing numbers.

In the crypto market, not all projects aim for long-term success. For some teams, their strategy is more like a playbook: first generate hype, then create a false image, and finally quickly cash out. This situation does exist in the crypto world. Projects use partner studios or market makers to artificially create liquidity, creating the illusion of a booming market. This is commonly referred to in the industry as "fake liquidity" or "wash trading."

The common process of project parties issuing coins to “cut leeks”:

- The first step is coin issuance and packaging. Using coin issuance tools like Four.meme and Pump.fun, project owners can generate a token with virtually no barriers to entry. Through a "pre-sale + automated launch" process, they create a seemingly standardized process. During this stage, common practices include "locking" and "burning limited partners," misleading the outside world into believing that liquidity is secure and reliable.

- The second step is to generate popularity and liquidity. Project owners need to make the token appear to be inherently popular from the outset. A common practice is to use bots to manipulate volume and create trading curves on DEXs, while simultaneously disseminating screenshots of "pre-sales sold out" and "active trading" in social media.

- The third step is to pump up the market and create sentiment. As prices rise, social media and other platforms begin to hype up the value of a particular coin, claiming it has increased dozens of times. Driven by FOMO (fear of missing out), external investors enter the market, becoming the real buyers.

- The final step is for the project to sell its holdings. This typically occurs in two ways: selling off reserved holdings in batches at a high price; or directly removing LPs and withdrawing the mainstream cryptocurrencies (BNB, USDT) from the pool. Either method often results in a sudden price drop, leaving only the retail investors who actually paid for the project.

From the outside, this process looks like a carefully choreographed performance: the stage has been set, the audience is drawn in, and the project team secretly decides the ending of the script.

Perfect cooperation between Web3 Studio and project parties

In this type of process, project owners don't work alone. They often collaborate with Web3 Studios, providing services like account resources, bulk new user acquisition, DEX liquidity pool construction, automated traffic generation, and promotional campaigns, making the entire process more feasible.

First, during the pre-sale phase, studios typically acquire a large number of registered user accounts through paid purchases, allowing them to quickly fill their quotas when pre-sale begins, creating a "sell-out-instant" atmosphere. Simultaneously, trolls will simultaneously push screenshots and messages to Telegram and WeChat groups, misleading the public into believing the project has garnered significant attention.

Secondly, there's the creation and packaging of a liquidity pool. Project owners need to inject liquidity on a decentralized exchange (DEX), and the studio provides technical support: helping configure the initial pool size and creating a sense of security through "pool lock tools" or "LP burn." These actions can easily be packaged as signs of a "fair launch" to bolster external trust.

Secondly, they create activity during the trading phase. Many studios are equipped with automated scripts that can create high-frequency trading volume on DEXs, creating the appearance of booming trading. At key price points, studios will also temporarily support the market to prevent a premature price crash. Furthermore, they will push trading curves and transaction screenshots to social media to further fuel hype.

Finally, in terms of publicity and promotion, the studio and the project party are divided into two parts: the project party is responsible for storytelling, while the studio is responsible for the specific implementation of attracting new customers, diverting traffic, fission and creating hot spots.

From an external perspective, the role of these Web3 studios is more than just "technical outsourcing." They are more like the "execution team" of the entire show, helping project owners package the launch of a new coin into a market event with "explosive popularity and active trading."

What are the legal risks for owners and employees of Web3 Studios?

If the project owner is the director of the show, then Web3 Studio is often the behind-the-scenes execution team. In fact, compared to the Web3 project owner, Web3 Studio faces higher legal risks. The reason is simple: most coin issuance projects are likely located outside of China. So, what criminal legal risks might those involved in Web3 Studio face? The following details potential criminal risks faced by Web3 Studio, including fraud, illegal fundraising, illegal business operations, aiding and abetting cybercrime, and money laundering.

Fraud risk. When a studio is aware of the project owner's deceptive intentions and still creates false impressions to help them raise funds or attract buyers, they may be considered accomplices. Typical scenarios include:

Knowing that the project party will not actually lock liquidity, but assisting in the promotion of "fake destruction" or "fake lock-up";

Knowing that the project owner planned to withdraw from the pool at a high level, they still helped create trading activity in the early stages and induced real investors to enter the market.

In some cases, this risk is no longer theoretical; it has been the subject of concrete criminal cases. For example, the widely publicized case of a post-2000 college student who issued Dogecoin and then withdrew it from a pool and was sentenced to four years and six months reveals this logic: projects inflate prices in the short term to attract buying, then withdraw liquidity from the DEX. When examining similar cases, judicial authorities often consider whether there was premeditated deception, whether the pool was withdrawn, and whether users were induced to participate as key factors in determining fraud.

Under this model, if a Web3 studio is deeply involved in actions such as "inflating the volume in the early stages," "creating false impressions," or "supporting the market," even if it is not a direct beneficiary, it may be held accountable for objectively committing fraud or other assisting behaviors.

Risk of illegal fundraising. For Web3 Studio, their actions may have included helping project owners "charge up" their quotas during the pre-sale phase, creating a "sell-out-instant" atmosphere. According to regulatory documents, any solicitation of funds from the general public, whether through token subscriptions, rebate promises, or "liquidity lock-up," without the approval of financial regulators may constitute the crime of illegally absorbing public deposits.

If the studio simply uses a large number of accounts it has purchased, effectively using its own funds or funds provided by the Web3 project, does this eliminate the risk? The answer is not absolute. Even if the studio uses a large number of accounts to purchase tokens to increase liquidity, its purpose is still to attract a large number of unspecified users to invest in project tokens.

Risk of illegal operations. Under domestic regulatory frameworks, virtual currency trading and related matching and market making are defined as illegal financial activities. If a studio establishes liquidity pools for project owners, manipulates trading pairs, or provides wash trading services, they are essentially engaging in unlicensed financial operations. For studio owners, this risk directly translates into criminal liability for "organizing and operating" operations. Employees who directly carry out these operations may also be considered "co-participants."

Risk of aiding information network criminal activities. Many studios maintain large numbers of real-name or virtual accounts, which they use for "new user acquisition," "bulk registration," and "proxy trading." If such behavior is deemed to facilitate fraud, money laundering, and other illegal activities, it could constitute aiding information network criminal activities. In some cases, even employees who simply provide technical interfaces or account resources can be held accountable.

Money laundering risk. When a studio helps a project convert tokens into USDT and then converts them into RMB, or facilitates cross-border fund transfers, if the fund flow is linked to illegal income, it will fall within the scope of money laundering.

Furthermore, from the perspective of principal and accessory, the owner of a Web3 studio often bears direct responsibility for "organization and planning." While employees, while responsible for execution, may also be considered accomplices if they knowingly carry out risky operations, they can also be considered accomplices. In other words, in this gray area, being "just an employee" is not a natural excuse for immunity.

Conclusion: Legal risks in the gray area

From the project's script, to the studio's collaboration, to the actual retail investors who pay the bills, this industry chain is repeated in the crypto world. But its existence does not mean it is safe.

While current laws don't explicitly address practices like "liquidity services" and "wash trading," judicial authorities are increasingly understanding virtual currency-related cases. As on-chain data analysis matures, capital flows and trading behavior are becoming increasingly traceable and quantifiable.

For Web3 Studios, this presents a reality: in the past, perhaps due to a lack of legal awareness of such activities, retail investors who filed a complaint to protect their rights might have been treated as simply a risk of cryptocurrency investment losses. However, in the future, this will likely be considered part of a series of illegal activities, including "assisting fraud," "illegal operations," and "aiding cybercrime." The boss, as the organizer, bears direct responsibility, while employees, knowingly operating with deceptive intent, will be considered accomplices.

In other words, the space for this type of gray market business is gradually shrinking. This article serves as a risk warning.

You May Also Like

Ethereum Ready For Round 2? Analyst Forecasts Early October Rally Amid $4,200 Retest

The US SEC has withdrawn its 19b-4 applications for tokens such as Solana, XRP, and Cardano, as well as Ethereum-collateralized ETFs.