Innovative people, stifling laws: the ‘mystery’ behind Libya’s tech space

Libya is not a country renowned for its tech vibrancy. Indeed, its name has long been associated with strife, conflict and instability, so not many people expect much innovation. But for many within the space, this is quite far from the truth.

According to Ibrahim Shuwehdi, Founder and CEO of e-commerce startup Mataa, considered one of Libya’s most promising startups, the country is much more stable than many other African countries. For him, the problem stems from poor storytelling.

“Since 2020, the country has been pretty much more stable than a lot of countries. The country just needs better marketing. Franchises are working well in the country, while the startup ecosystem is still working its way since it needs more than stability for the capital to come,” Shuwehdi said.

He added that Libya has a unique advantage in its geography and demographics, as its culture is closer to the “Middle East” than the “Western Arab countries”. The country is also closer to African countries than other Arabian countries, so its startups can truly serve both regions.

See also: ‘Many Sudanese have never used Google’- viewing Sudan’s tech isolation through the eyes of Tarneem Saeed

Ibrahim Shuwehdi, Founder/CEO of Mataa

Ibrahim Shuwehdi, Founder/CEO of Mataa

In reality, the North African country is not a technologically backward state by any stretch of the imagination. It enjoys one of the widest internet penetration rates on the African continent, with 88.5 per cent of the population having access to strong 4G internet.

For emphasis, Nigeria has just 41 per cent, Kenya has 48 per cent, while South Africa boasts 79 per cent. These are the 3 largest tech ecosystems in Africa.

Indeed, Libya has had 5G internet since 2019, making it one of the first African countries to enjoy the premium technology. Data prices are also low. To add, smartphone penetration is quite healthy, with 14.6 million active mobile cellular connections as of January 2025.

This is nearly double the country’s population of 7.45 million.

Essentially, while the population might be small, it is massively underserved. When coupled with the high purchasing power of the average Libyan, it is a market ready to be explored.

The trouble with Libya’s tech space

The biggest challenge hindering the growth of Libya’s tech ecosystem, according to Ibrahim Shuwehdi, is an archaic legal system that is not business-friendly. The country runs a hybrid legal system.

The framework is comprised of a mix of Sharia, civil law traditions, and political influence. These factors all shape the way justice is delivered.

Aside from the multifacetedness of its judiciary and legal system, which leads to conflicting outcomes, there is also systemic corruption in the business and legal space, and this presents a major obstacle to doing business.

Libya ranks 164th out of 190 in the World Bank’s Starting a Business Index and 186th out of 190 in its Ease of Doing Business rankings. This is largely owing to the nature of its business laws. For instance, recent changes to the laws require foreign-owned businesses to seek local partners with at least 51 per cent ownership to register.

Similarly, bringing in products or services requires going through a local player.

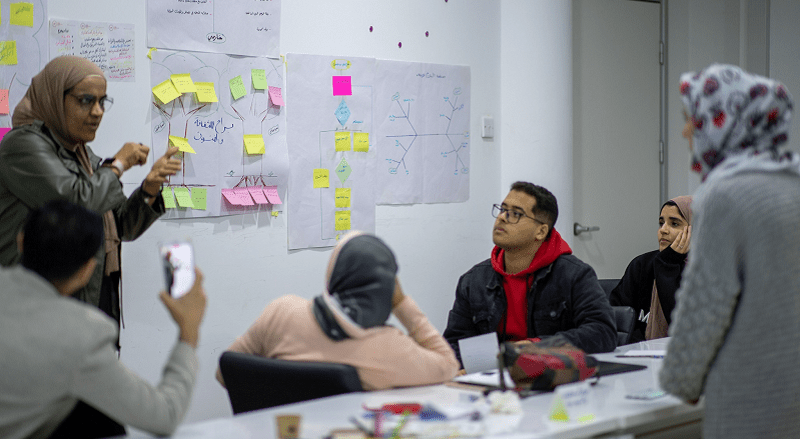

A Libyan Tech Hub

A Libyan Tech Hub

It gets worse. The ecosystem is battling a foreign currency liquidity crisis. Consequently, foreign companies often seek payment up front before introducing products and services into the country.

Libya has an extensive list of United Nations sanctions. As a result, some top citizens, politicians, military chiefs and their affiliates are subjected to asset freezes and travel bans. Hence, businesses seeking to launch in the country must confirm that their prospective partners are not on the UN sanction list before engaging them.

“These are laws from past decades that are not adjusted to the new way of working,” Shuwehdi said.

The Libyan tech ecosystem is stymied by a lack of access to VC funding

Ordinarily, these factors should engender the rise of homegrown tech startups that are providing solutions to local problems. Yet, this rise suffers under the heels of a paucity of VC funding.

According to Ibrahim, the same laws that are crippling the business space are affecting the entry of venture capital. “Global investors will not enter because the country’s laws are still old and not up to date, not because of instability,” he told Technext.

Without access to foreign capital, startups have to rely on local investors. Other common sources of funding are mostly from grants from NGO’s like e fundsforNGOs and SPARK, and an EU-funded project called Libya Start-up.

Mr Shuwehdi, however, believes grants like the EU fund do more harm than good to the space as they do not encourage a proper incentive-reward cycle.

“The EU funds actually hurt the startups they are claiming to help, because the incentive-reward cycle is broken. Have you heard of a successful venture that was raised from an EU FUND? There are a lot of investing stories within the country, but still more of a private equity style than venture capital,” he said.

Yet, the ecosystem has a few success stories.

In July, Mr Shuwehdi’s e-commerce startup, Mataa, raised Libya’s first-ever venture funding round, valued at above $100,000. The round, whose actual value Technext can confirm is more than $1 million, resonated through the ecosystem and brought the North African country to the limelight.

Speaking about what that funding round meant for the Libyan tech space, CEO Ibrahim Shuwhedi said: “The round has a huge impact on the country for sure, it breaks a lot of ice and will have more venture funding to try the market.”

Shuwehdi narrated that Mataa’s journey has been hard from the beginning. Coupled with the earlier listed challenges, founders face a paucity of mentors and collaborators. Thus, most founders bootstrap as they go operational.

For instance, Ibrahim is building the foundational blocks of his operational system one day at a time: the team handles last-mile delivery, manages stock, processes and stores data, and even helps vendors with cash collections.

In the midst of these, Mataa has grown to become the biggest player in the country’s e-commerce space. Yet, it doesn’t consider itself successful. But the startup’s strategy is to leverage these challenges to succeed.

“These same problems are actually what inspired us to start because from such disadvantages come great opportunities,” he said. “The plan is to dominate the Libyan e-commerce market, then expand into the region using strong Libyan characteristics,” he said.

Yet, he believes that the Libyan startup ecosystem has the potential to dominate Africa someday. As such, he advised African founders interested in expanding into the MENA region to consider Libya as the gateway.

You May Also Like

BitMine koopt $44 miljoen aan ETH

Upbit hack sparks altcoin season in Korea? Thailand targets WLD