Vitalik’s latest article: Why can open source promote technological equality?

By Vitalik Buterin

Compiled and edited by Janna and ChainCatcher

ChainCatcher Editor's Summary

This article is from Vitalik Buterin's personal website, which primarily publishes his blog posts, opinions, and research, covering topics such as blockchain technology, cryptoeconomics, decentralized governance, and privacy protection. This article explores how open source technology can promote fairness and transparency, why emerging technologies may exacerbate inequality, and open source as a "Schelling point" for technology governance.

ChainCatcher organized and compiled the content (with some deletions).

Core ideas:

- Radical technologies may exacerbate social inequality because they are more accessible to the rich and powerful, leading to gaps in life expectancy and advantages between the rich and the poor, and even the formation of a global underclass.

- Another form of technology abuse is when manufacturers project power over users through data collection, hiding information, etc., which is fundamentally different from unequal access to technology.

- Open source is an underrated third path that improves equality of access and producer access to technology, enhances verifiability, and eliminates vendor lock-in.

- Opponents of open source believe that it carries a risk of abuse, but centralized gatekeeper control is untrustworthy, prone to abuse for military and other purposes, and difficult to ensure equality between countries.

- If the technology carries a high risk of misuse, the better solution may be not to implement it; if the risk is uncomfortable due to power dynamics, open source approaches can make it fairer.

- Open source does not mean laissez-faire. It can be combined with laws and other regulations. The core is to ensure the democratization of technology and the accessibility of information.

One concern we often hear is that certain radical technologies could exacerbate power inequalities because they are inevitably limited to the rich and powerful.

Here's a quote from someone who's expressed concern about the consequences of longer lifespans:

“Will some people be left behind? Will we make society even more unequal than it already is?” he asks. Tuljapurkar predicts that the surge in lifespan will be limited to wealthy countries, where citizens can afford anti-aging technologies and governments can fund scientific research. This disparity further complicates the current debate over access to healthcare, as the gap between rich and poor widens not only in quality of life but also in how long they live.

“Big Pharma has a track record of being very demanding in terms of providing products to people who can’t pay,” Tuljapurkar said.

If anti-aging technologies are distributed in an unregulated free market, “it seems entirely possible to me that we could end up with a permanent global underclass, where countries are locked into today’s mortality rates,” Tuljapurkar says. “If that happens, you’ll get a negative feedback loop, a vicious cycle. Those countries that are excluded will always be excluded.”

Here’s an equally strong statement from an article concerned about the consequences of human genetic enhancement:

Earlier this month, scientists announced they had edited genes in human embryos to remove a disease-causing mutation. This remarkable work is the answer to many parents' prayers. Who wouldn't want the chance to prevent their children from suffering that's now avoidable?

But this won't be the end. Many parents want to ensure their children have the best advantages through genetic enhancement. These technologies are now accessible to those who can afford them. With this increased capability comes ethical concerns that outweigh the ultimate safety of such technologies. The high cost of these procedures will create scarcity and exacerbate already growing income inequality.

Similar views in other technology areas:

- Digital technology overall: https://www.amnestyusa.org/issues/technology/technology-and-inequality/

- Space Travel: https://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/What-Does-Billionaires-Dominating-Space-Travel-Mean-for-the-World.html

- Solar geoengineering: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/global-sustainability/article/hidden-injustices-of-advancing-solar-geoengineering-research/F61C5DCBCA02E18F66CAC7E45CC76C57

This theme runs through many critiques of new technologies. A related, but fundamentally different, theme is the use of technology products as tools for data collection, vendor lock-in, the deliberate hiding of side effects (as Moderna’s vaccines have been criticized for), and other forms of abuse.

New technologies often create greater opportunities for people to access things without granting them rights or full information about them, so from this perspective, older technologies often appear more secure. This is also a form of technology strengthening the powerful at the expense of others, but the problem is the power that manufacturers project on users through technology, not the unequal access in the previous examples.

I'm personally very pro-technology, and if the choice is a binary one of "push further" vs. "maintain the status quo," I'd happily push forward with everything except a very few things (like gain-of-function research, weapons, and superintelligent AI), despite the risks.

That’s because the benefits, overall, are longer and healthier lives, more prosperous societies, greater human relevance in an age of rapid AI advances, and cultural continuity maintained through older generations as living people rather than memories in history books.

But what if I put myself in the shoes of someone who is less optimistic about the positive impacts, or more concerned about the ways in which powerful individuals will exploit new technologies to dominate the economy and exert control, or both? For example, I already feel this way about smart home products: the benefits of being able to talk to my lightbulbs are outweighed by my reluctance to hand over my personal life to Google or Apple.

If I adopt a more pessimistic assumption, I can also imagine myself feeling similarly about certain media technologies: if they allow the powerful to broadcast information more efficiently than others, then they can be used to exert control and drown out others, and for many of these technologies, the gains we get from better information or better entertainment will not be enough to compensate for the way they redistribute power.

Open Source as a Third Path

I think one perspective that is greatly underestimated in these situations is to only support technologies that are developed in an open source manner.

The argument that open source accelerates progress is very plausible: it makes it easier for people to build on each other's innovations. At the same time, the argument that requiring open source slows progress is also very plausible: it prevents people from using a host of potential profit strategies.

But the most interesting consequences of open source are those that have nothing to do with the speed of progress:

- Open source improves equality of access. If something is open source, it is automatically accessible to anyone in any country. For physical goods and services, people still pay marginal costs, but in many cases, proprietary products are priced high because the fixed costs of inventing them are so high that they don't attract more competition. Therefore, marginal costs are often quite low, as is the case in the pharmaceutical industry.

- Open source improves equality of access for those who become producers. One criticism is that giving people free end-products doesn't help them gain the skills and experience needed to climb the global economy into prosperity, which is a truly reliable guarantee of a lasting quality of life. Open source doesn't do that; it essentially enables anyone, anywhere in the world, to become a producer, not just a consumer, at every step of the supply chain.

- Open source improves verifiability. If something is open source, ideally including not only the output but also the process of inventing it, parameter choices, and so on, it’s easier to verify that you’re getting what the provider claims, and for third-party research to identify hidden flaws.

- Open source eliminates the chance of vendor lock-in. If something is open source, the manufacturer can't render it useless by remotely removing functionality or simply going bankrupt, as is the case with highly computerized/connected cars that wouldn't work if the manufacturer shut down. You always have the right to fix it yourself or request a different provider.

We can analyze this through the lens of some of the more radical techniques listed at the beginning of the article:

- If we had proprietary life extension technology, it would likely be limited to billionaires and political leaders, though I personally expect the price of this technology to drop rapidly. But if it were open source, anyone could use it and make it available to others cheaply.

- If we had proprietary human genetic enhancement technology, it would likely be limited to billionaires and political leaders, creating an upper class. Again, I personally believe such technology will spread, but there will undoubtedly be a gap between what the wealthy and ordinary people have access to. However, if it were open source, the gap between what the well-connected and powerful have access to and what everyone else has access to would be much smaller.

- For any biotechnology overall, an open-source scientific safety testing ecosystem is likely to be more effective and honest than companies endorsing their own products and having them rubber-stamped by compliant regulators.

- If only a few people can go to space, then depending on political trends, some of them might have the opportunity to monopolize an entire planet or moon. If the technology is more widely distributed, their chances of doing so will be smaller.

- If smart cars were open source, you could verify that the manufacturer wasn't spying on you and not be dependent on the manufacturer for continued use of the car.

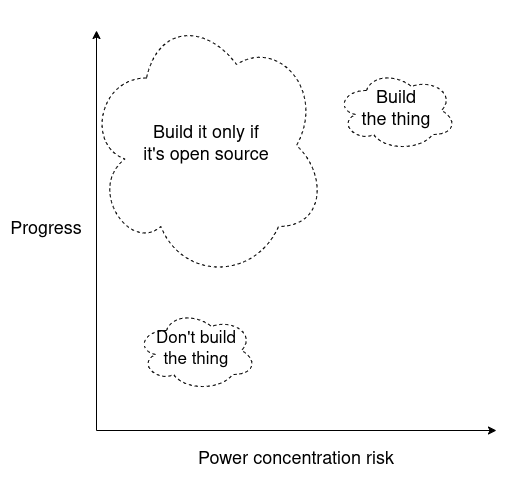

We can summarize the argument in a diagram:

Note that the bubble for "Build it only if open source" is wider, reflecting greater uncertainty about how much progress open source will bring and how much risk of concentration of power it will prevent. But even so, in many cases it's still a good deal on average.

Open Source and the Risk of Abuse

A major argument sometimes raised against open-sourcing powerful technologies is the risk of zero-sum behavior and non-hierarchical forms of abuse. Giving everyone nuclear weapons would certainly end nuclear inequality. This is a real problem, as we've seen multiple powerful nations exploit asymmetric nuclear access to bully others, but it would also almost certainly lead to billions of deaths.

As an example of negative social consequences without intentional harm, giving everyone access to plastic surgery could lead to a zero-sum game of competition, where everyone expends vast resources and even risks their health to be more beautiful than others. Ultimately, however, we all become accustomed to higher levels of beauty, and society isn't truly better off. Some forms of biotechnology could potentially produce similar effects on a large scale. Many technologies, including many biotechnologies, fall somewhere between these two extremes.

"I only support it if it's carefully controlled by trusted gatekeepers." This is a valid argument for moving in the opposite direction. Gatekeepers can allow positive use cases for the technology while excluding negative ones. Gatekeepers can even be given a public mandate to ensure non-discriminatory access to everyone who doesn't violate certain rules.

However, I have a strong, implicit skepticism about this approach. Primarily, I doubt that trusted gatekeepers even exist in the modern world. Many of the most zero-sum and riskiest use cases are military, and the military has a poor history of disciplining itself.

A good example is the Soviet biological weapons program:

Given Gorbachev's restraint regarding SDI and nuclear weapons, his actions related to the Soviet Union's illegal biological weapons program are puzzling, Hoffman noted. When Gorbachev came to power in 1985, despite being a signatory to the Biological Weapons Convention, the Soviet Union already had an extensive biological weapons program initiated by Brezhnev. In addition to anthrax, the Soviet Union was also researching smallpox, plague, and tularemia, but the intent and objectives of these weapons were unclear.

“The Kateyev documents show that there were multiple Central Committee resolutions in the mid-to-late 1980s regarding the biological warfare program. It’s hard to believe that these were signed and issued without Gorbachev’s knowledge,” Hoffman said.

“There’s even a memorandum to Gorbachev from May 1990 about the biological weapons program – and that memo still doesn’t tell the whole story. The Soviets misled the world, and they misled their own leaders.”

The Russian Biological Weapons Program: Vanished or Disappeared? argues that the biological weapons program may have been provided to other countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Other countries have also made significant mistakes and need to explain themselves. I need not mention all the countries involved in gain-of-capability research and the exposure of its inherent risks. The history of weaponized interdependence in digital software, such as finance, shows how easily what is intended to prevent abuse can slip into the unilateral projection of power by operators.

This is another weakness of gatekeepers: by default, they will be controlled by national governments, whose political systems may have an incentive to ensure equal access within countries, but no powerful entity has a mandate to ensure equal access between countries.

To be clear, I’m not saying that gatekeepers are bad, so let’s go free, at least not for gain-of-function research. Instead, I’m saying two things:

If something has enough risk of "everyone-to-everyone abuse" that you're only comfortable doing it in a locked-down fashion with centralized gatekeepers, consider that the right solution might be to not do it at all and invest in an alternative technology with a better risk profile.

If something has enough "power dynamics" that you simply aren't currently comfortable seeing it proceed, consider that the right solution is to do it, and do it in open source so that everyone has a fair chance to understand and participate.

Also note that open source doesn't mean laissez-faire. For example, I favor open source and open science approaches to geoengineering. But this isn't the same as "anyone can go and divert rivers and spray whatever they want into the atmosphere," and in practice it won't lead to that: laws and international diplomacy exist to make such actions easily detectable, making any agreement fairly enforceable.

The value of openness is to ensure that technology is democratized, available to many countries rather than just one; and to increase access to information so that people can more effectively form their own judgment about whether what they are doing is effective and safe.

Fundamentally, I see open source as a way to achieve the strongest Schelling point in technology with less risk of concentrated wealth, power, and information asymmetry. Perhaps we can try to build clever institutions to separate the positive and negative effects of technology, but in the messy real world, the most likely approach is to ensure the public's right to know—that is, to ensure that things happen in the open, so that anyone can understand what's happening and participate.

In many cases, the immense value of accelerating technological progress far outweighs these concerns. In a few cases, it is crucial to slow technological progress as much as possible until countermeasures or alternative ways of achieving the same goals become available.

However, within the existing framework of technological development, the incremental improvements brought about by choosing open source as a way of technological progress are a third option: an underrated approach that focuses less on the rate of progress and more on the style of progress, and uses the expectation of open source as a more acceptable lever to push things in a better direction.

Bunları da Bəyənə Bilərsiniz

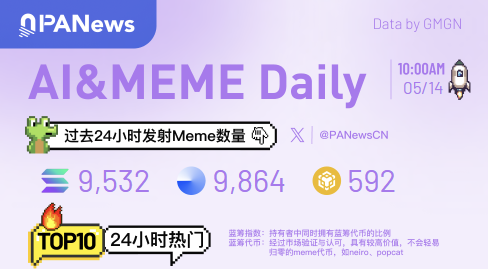

Ai&Meme Daily, a picture to understand the popular Ai&Memes in the past 24 hours (2025.5.14)

A certain address bought over 1,700 WETH at a low price of $4,646.4 this morning.